Other November 24, 2025

Why do Brazilians speak Portuguese and not Spanish?

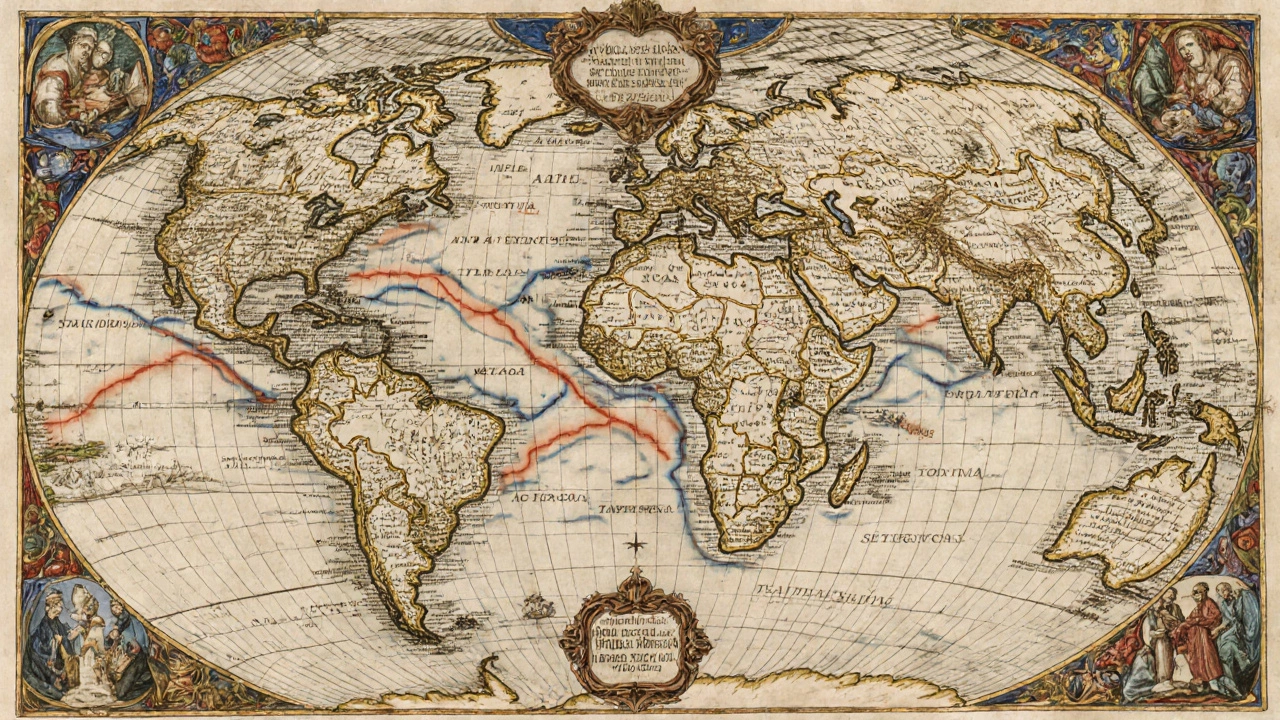

Tordesillas Treaty Timeline

Why Brazil Speaks Portuguese

Explore the key historical events that made Brazil the only Portuguese-speaking country in South America.

The Pope drew a line through the Atlantic Ocean, dividing the New World between Spain and Portugal. Brazil fell east of the line, becoming Portuguese territory.

Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral accidentally landed on Brazil's coast, establishing the first Portuguese presence.

Portugal established schools, churches, and legal systems in Portuguese, making it the only language for government, commerce, and education.

Brazil declared independence from Portugal, but chose to keep Portuguese as the official language. No movement to adopt Spanish occurred.

Key Insight

Brazil speaks Portuguese not because of cultural preference, but because a treaty drawn in 1494 placed it on Portugal's side of the world. Geography, timing, and colonial policies made Portuguese the only viable language for Brazil's development.

It’s one of those questions that pops up when you’re watching a Brazilian soccer match and hear the commentators speak a language that sounds like Italian mixed with Spanish-but it’s not Spanish. It’s Portuguese. And it’s the only language spoken by over 200 million people in Latin America that isn’t Spanish. Why? The answer isn’t about culture, religion, or geography. It’s about borders drawn by kings centuries ago.

It started with a line on a map

In 1494, Spain and Portugal were the two biggest sea powers in Europe, both racing to claim new lands after Columbus’s voyage. Neither wanted war over territory they hadn’t even seen yet. So they went to the Pope for help. He didn’t send armies-he sent a line. The Treaty of Tordesillas split the world in half. Everything west of a line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands went to Spain. Everything east went to Portugal.

That line cut through South America. Brazil, which was then just a stretch of jungle and coastline, fell east of the line. That made it Portuguese. Everything else-the Andes, the Amazon basin west of the river, the Pampas-fell on the Spanish side. So when Portuguese explorers landed in what’s now Salvador and Rio de Janeiro, they didn’t just bring goods and missionaries. They brought their language. And it stuck.

Spain didn’t ignore Brazil-it just never got there

You might think Spain could have just marched in and taken Brazil later. But geography and timing made that impossible. The Portuguese got there first, in 1500, when Pedro Álvares Cabral accidentally sailed off course and landed on the Brazilian coast. By the time Spain realized what was happening, Portugal had already set up trading posts, started logging brazilwood (which gave the country its name), and brought over settlers.

Spain was busy elsewhere. They were conquering the Aztecs in Mexico, the Incas in Peru, and building empires in Colombia and Argentina. Brazil was too far east, too dense, and too far from their main routes. Spain didn’t have the manpower or interest to fight Portugal for a land they didn’t even know was valuable.

Portugal built a system that locked in their language

It wasn’t enough to just arrive. Portugal made sure Portuguese stuck. They didn’t just trade-they colonized. They brought Catholic priests who taught in Portuguese. They set up schools for the children of settlers and mixed-race families. They made Portuguese the only legal language for government, law, and commerce.

Unlike in some Spanish colonies, where indigenous languages survived in remote areas, Brazil had fewer large, centralized indigenous empires. The Tupi-Guarani languages were spoken by many groups, but they were scattered. Portuguese didn’t have to replace a single dominant language-it replaced dozens, often by simply being the only language that mattered for survival, trade, or upward mobility.

By the 1700s, even indigenous people and enslaved Africans adopted Portuguese. It became the common tongue. The slave trade brought millions from West Africa, and they learned Portuguese to communicate with each other and their owners. Over time, it became the language of the streets, the markets, the homes.

Independence didn’t change the language

When Brazil declared independence from Portugal in 1822, it didn’t switch to Spanish. Why would it? Portuguese was already the language of the elite, the military, the courts, and the press. The first emperor, Dom Pedro I, was born in Portugal but raised in Brazil. He spoke Portuguese. His ministers spoke Portuguese. The constitution was written in Portuguese.

There was no movement to adopt Spanish. No nationalist group said, “Let’s become more Latin by speaking like our neighbors.” In fact, Brazilians saw themselves as different from the Spanish-speaking countries. They had their own identity, their own culture, their own music and food. Language was part of that difference. Switching to Spanish would’ve meant erasing their history, not building a new one.

Spain’s colonies did the same thing-just differently

Spanish-speaking countries didn’t have a single origin story either. In Mexico, Spanish replaced Nahuatl. In Peru, it replaced Quechua. In Argentina, it replaced Guaraní. But they all followed the same pattern: conquer, convert, control. The difference was who did the conquering.

Portugal didn’t conquer Brazil because it was weak. It conquered because it was lucky-with the Pope’s line, with timing, with geography. Spain didn’t lose Brazil because it was slow. It just never had a reason to fight for it.

Modern Brazil still speaks Portuguese-and it’s proud of it

Today, Brazil is the largest Portuguese-speaking country in the world. It has more Portuguese speakers than Portugal itself. It’s the only country in South America where Portuguese is the official language. And Brazilians don’t see it as a relic of colonialism-they see it as their own.

They’ve changed it. Brazilian Portuguese has its own accent, slang, grammar quirks, and rhythm. Words like “você” (you) and “ônibus” (bus) sound different from European Portuguese. They use “tchau” instead of “adeus.” They drop subject pronouns more often. Their intonation is musical. It’s not just Portuguese-it’s Brazilian Portuguese.

When Brazilians travel to Spain or Argentina, they often say they can understand the language but can’t always follow the speed or slang. And Spaniards say the same thing about Brazilian Portuguese. It’s like British and American English-same root, different flavor.

Why not Spanish? Because history wrote the script

There’s no secret code, no hidden conspiracy, no cultural rebellion. Brazil speaks Portuguese because a treaty drawn by a pope in 1494 placed it on the Portuguese side of a line on a map. That line became a border. That border became a nation. And that nation built its identity around the language of its colonizers.

It’s not about superiority. It’s not about better education or smarter people. It’s about accidents of geography, timing, and politics. Spain had its empire. Portugal had its piece. And Brazil? Brazil got the language that came with the land.

Next time you hear a Brazilian speak, remember-it’s not a mistake. It’s history.